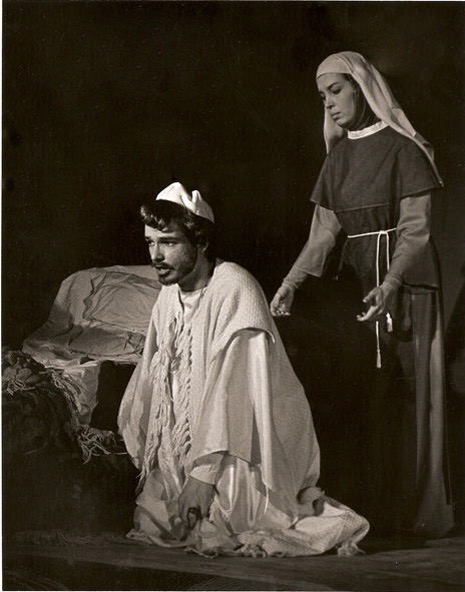

The Bishop (with Linda Rasmussen as The Nun)

According to religious tradition, the Children's Crusade was a mass movement, begun in the year 1212, in which a lone shepherd boy, having had instructions from Jesus in a vision, through the force of his faith and personality gathered thousands of children and prepared to lead them to Palestine with the intention of conquering it for Christianity and of recovering the True Cross. In this version, the children’s movement spread with heaven-directed alacrity throughout Europe, attended by miracles, and was even blessed by Pope Innocent III, who is supposed to have proclaimed that the faith of these extraordinary young ones "put us all to shame."

The charismatic boy who fronted this movement was universally recognized as a living saint. Some 30,000 human beings were ostensibly involved in his crusade, most of them twelve years of age or younger. These innocent marchers traveled southward towards the Mediterranean, where, they had been led to believe fervently, the sea would part to enable them to march straight on to Jerusalem unimpeded, just as the Red Sea had opened so that Moses could lead his flock out of Egypt. When this miracle did not occur, several merchants gave passage on seven ships to as many of the children as the vessels could hold. However, the children were either taken to Tunisia and sold into slavery or died in a shipwreck on the island of San Pietro (off Sardinia) during a gale. In some accounts, they never even reached the sea before dying of starvation or giving up their crusade because of exhaustion.

A later view, not entirely divorced from the traditional one, holds that there were actually two similar movements in 1212, one in France and the other in Germany. These came to be merged together in the legend of the Children's Crusade. Both were inspired by young boys who had visions. Although the common people held the same strong feelings of piety and religiosity that had earlier moved nobles to take up the Cross in the eleventh century (the year 1096 is generally accepted as that in which the First Crusade was planned and began to be implemented), they did not have the finances, equipment, or even general physical strength to go anywhere themselves. The repeated failures of earlier crusades frustrated those who held the hope of recovering the True Cross and liberating Jerusalem from the "infidel" Muslims, and this frustration led to the unusual events attributed to the year 1212. (How sad to note that the succeeding eight centuries have not made much difference in the fundamental antipathy between Christians and Muslims.)

In the first children’s movement, Nicholas, a ten-year-old shepherd from Germany, led a group across the Alps and into Italy in the early spring. Hundreds—and then thousands—of children, but also adolescents, women, the elderly, the poor, parish clergy, and a fair share of petty thieves and prostitutes, joined him in his march south. He indeed believed that God would part the waters of the Mediterranean so that his “army” could walk across the dry seabed all the way to Jerusalem to convert the Muslims with love (a great departure from the earlier belief that the children were warriors who would “conquer”). The common people of southern Europe greeted the marchers as heroes when they passed through the towns and villages, but the educated class and the clergy criticized them as being deluded. In August, Nicholas's group, which had splintered in the course of its long trek, reached Lombardy and various port cities. Nicholas himself arrived with a large contingent at Genoa on 25 August 1212. To their great disappointment the sea did not open for them, nor, alternatively, did it allow them to walk across the waves to their destination. From this disillusionment (Jesus walked on water, why could they who adored him not also do so?), many set out to return to their homes. Most did not make it back that far. Others remained in Genoa. Some appear to have marched on to Rome, where the embarrassed Pope Innocent III indeed praised their zeal but released them from their vows as crusaders and sent them away. Although the Pope did not encourage them to continue their march, stories of their faith may have stimulated future efforts by official Christendom to launch further crusades. Nicholas’s fate is unclear. Some sources state that he eventually joined the Fifth Crusade, others that he died in Italy.

The alleged second movement was led by twelve-year-old shepherd Stephen de Cloyes, who originated near the village of Châteaudun in France. He claimed, in June 1212, that he bore a letter from Jesus to the French king. Stephen had met a pilgrim who asked for bread. When Stephen provided it, the beggar revealed himself to be Jesus and gave the boy the letter, designating it to be for the reigning monarch, Philip II. The contents of the unpreserved letter are unknown, but it is clear that the king, who had already been to the Holy Land, was loath to lead another crusade. Still, Stephen attracted a large following, which he led to Saint-Denis, where he was reportedly seen to work miracles. However, on the advice of clerics of the University of Paris and on the orders of King Philip, Stephen’s followers were commanded to disperse back to their homes. Apparently, most of them obeyed. None of the contemporary accounts mentions this band as having headed on to Jerusalem. This leaves us with the original theory of one boy, one crusade, that of Nicholas, many members of whose army of disciples are at least credited with beginning the sea journey. Legends of both miracles and tragedies (being forced into slavery or drowning en route) associated with the Children's Crusade abound, and the actual events continue to be a subject of earnest debate among historians. Though modern scholarship has challenged, in particular, the traditional view, asserting that the Children's Crusade was neither a true crusade nor made up of an army of children, and that the Pope did not call for it, nor did he bless it, it does acknowledge an historical basis for the legend. Namely, it was an unsanctioned popular movement, the beginnings of which are shrouded in uncertainty and the ending of which is just as difficult to pinpoint.

Whatever the impenetrable truth of it, the Children's Crusade has inspired numerous works of art, literature, and music, none more powerful and deeply moving than Gian-Carlo Menotti’s The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi. The composer was inspired by a passage in Adolf Waas’s History of the Crusades (Freiburg: Herder & Co., 1956) that reads, in part: “Shortly before the Fifth Crusade (1218–1221), almost simultaneously from France and Germany, unarmed children set out to liberate the Holy Land.…It is difficult…to understand that after the deaths of so many men, children believed that God had chosen them to liberate Jerusalem without weapons: through the failure of the former Crusades, He seemed to have indicated that He disapproved of a struggle for the Holy City by force of arms. Even less can we understand…that grown-ups shared in this belief and assisted in the departure of the children.”

The title page of G. Schirmer’s piano-vocal score of The Bishop does not designate the genre of Menotti’s creation. According to numerous encyclopedia entries, the composer called it a dramatic cantata, though important others do label it an opera. The Bishop is so theatrical and involving that it cries out to be staged, and since its world premiere (in a concert performance at the May Festival in Cincinnati in 1963), that seems to be the way it is most often presented. The resources required (including two full choruses, one of adults and one of children) are not quite modest enough to make it as easy for an amateur society to put on as, say, the same composer’s Amahl and the Night Visitors (which needs one small group of choristers and a few dancers). From time to time, the two works are played on the same bill (for instance, Anne Arundel College in Maryland did this in 2008), a juxtaposition that in my opinion betrays both. The pairing dilutes the very potent emotional impacts of the individual works, and as a matter not only of personal taste but also of aesthetic judgment, I believe each should be heard on its own—short evening though this makes in both cases—or with a vastly different companion piece. (In 1969, the North Carolina School of the Arts did The Bishop in a double bill with Orff’s Carmina Burana, which strikes me as a particularly valid and imaginative coupling because both works deal with the Middle Ages, if from quite opposing perspectives.)

The composer turned fifty-two not long after that 1963 Cincinnati premiere, and though he wrote a great deal more music for the stage (he died at ninety-five on 1 February 2007), his Bishop of Brindisi was the last genuine triumph of his career, the last work acclaimed and universally commended not just by its first audience but by the professional commentators present to hear it as well. Like all else Menotti ever wrote that had text, the words are his own. The poetry is rather extraordinary, the thoughts and feelings it expresses not purveyed in easily grasped phrases, and it imposes a profound obligation upon the singers, particularly the interpreter of the Bishop (who has the most to sing and myriad philosophical musings to convey), to make ourselves understood. If there is anything in which I can take special pride, it is that on the recording made from the local radio broadcast (this production took place in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1974) every word I sang can be clearly comprehended. Responses to the performance over the years have invariably begun with that observation. It was included in the immediate reaction of those present on the live occasion itself. I remember the audience members approaching afterward in all manner of moods, from the lady, still visibly shaken, who said simply, “I don’t know when I have ever been so moved by anything,” and then hurried away, to the one who exclaimed in apparent astonishment, “I understood every last word!” The reason for the first statement, of course, is Menotti himself, who poured not just heart and soul and, ultimately, perhaps a sense of hope, but all his doubts about God, faith, and man’s place and duties in the cosmic scheme (if, indeed, there is such a thing and it is “directed”) into his score, each episode of which strikes exactly the right musical and textual mark to channel not only his characters’ deepest feelings but to reveal the composer’s own as well.

For the second factor, presenting the words with complete intelligibility within a secure musical line, I believe I am justified in taking credit. The legato harks back to those boy soprano days of “singing like Zinka”; the ability to float a thorny, consonant- and archaic-word-laden text in English within it I’ll chalk up to success at doing the hard job of learning the craft that has to be invisible (or inaudible or not obvious, however you look at it) when on the stage to create a character. That would be any character, indeed, but so tormented and voluble a one as Menotti’s dying Bishop most especially. The reception I found for this effort far exceeded anything I had previously experienced anywhere. I remember telling my then partner, Peter Bugel, “In Fort Worth, they treated me as if I were a great artist.” It would be impossible to forget the generosity of his response: “You are a great artist, Bruce, you mustn’t think of it as something you ‘got away with’ in Texas!”

It helps, of course, to have so fine a colleague as the wonderful mezzo Linda Rasmussen (a lifelong friend, met in grad school in Boston) in the other role, the doctrinaire but not unsympathetic nun who cannot immunize the Bishop against his doubts and fears with her impregnable, unexamined thirteenth-century faith, who enjoins him not to ask “vain questions,” and who finally tells him just to say his prayers because he’s about to die. Linda was able to temper the Sister’s rigidity through her lovely tone and serene manner.

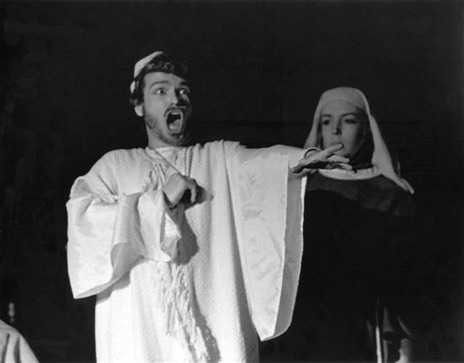

The story is heartbreaking. A group of children arrive at the port of Brindisi on their way to the Middle East (“Sleeping together under lonely moons, we feared no wolf or eagle, for we come by God’s command to free His tomb in Holy Land”). They ask for the local bishop’s blessing upon their crusade. He is intensely reluctant to grant it. The populace, virtually intoxicated by the children and their faith, demands that the cleric bless them, repeatedly enjoining him, “Give them your blessing! Let them depart!” With grave doubt and anxiety he grants his blessing, under darkening skies. The children, singing joyfully, board the waiting ships and set sail. A terrible squall blows up and before the vessels have disappeared over the horizon, they flounder and sink. The children are heard calling for aid, for their mothers, and for God before perishing. The townspeople, to whom he capitulated and gave exactly what they demanded, immediately turn on the Bishop: “Cursed be the shepherd who leads his flock to death! Stone his palace, burn his books, break his staff, and cast his ring into the sea. Let him walk naked, a man among men.”

It is these events the Bishop relives in guilt and horror, as he has done each sleepless night since their occurrence, during his protracted onstage death. His initial utterance—the first phrase sung in the opera—shows us his fear and dread: “And now the night begins.” So many of Menotti’s words, and the simple but heartrending melodic prosody in which they are couched, haunt me to this day:

--Give me an enemy to kill, O Lord, but not a child to help!

--Do not call for help, my children. Love has no wings and faith is fallible.

--Many are the innocents who call for help, but God has made Pilates of us all.

Although it was apparently foreordained that my association with The Bishop would be limited to one production, it did not always seem that such would be the case. A musician acquaintance of an acquaintance in New York had studied with both Menotti and his protégé, Thomas Schippers, and was familiar with the opera, which he loved, from its incarnation on a 1964 RCA Victor recording. He was very interested in hearing any other audio version that might exist. The role of the Bishop had been created by the twenty-seven-year-old lyric bass Richard Cross, a Menotti favorite, but the recording, which is what made the work known to the music-loving public in general, featured the great heroic bass-baritone George London, toward the end of his career, after vocal troubles had set in. London’s voice and manner conjure an aging Wotan striding the crags surrounding Valhalla, or the corrupt, guilt-ridden Boris Godunov railing at the Duma, not the aesthetic little Bishop whose faith has been sorely tested by what he perceives as the results of his coerced blessing of some fanatic children demanding to have their mission consecrated by one of God’s intercessors. True, the man is as guilt-ridden as Boris, but in his case the deaths for which he feels responsible were in no way intended by him. His conscience is rent because of his faith, not because he has with forethought committed murder, and he very specifically must remain poignantly human and ought not to be made “larger than life” in the way operatic gods and tsars must be.

Upon hearing the recorded Fort Worth performance (several years after it took place), the young conductor mentioned above asked for a copy of the reel-to-reel tape, which he carried—along with several of the photographs seen on this and the ensuing page—to the composer at his Spoleto USA Festival in Charleston, South Carolina. Menotti’s schedule did not permit him to listen to it for quite some time, but more than a year after the tape was presented, the report came back to my personal management (at the time, Sara Tornay) from his representative that he was deeply moved to hear a younger sounding, lighter-voiced Bishop than the one of his original conception—despite one particular shortcoming at the bottom extreme of the required vocal range, a low F-sharp that I did not dodge but could only phonate, not resonate—and to see what the artist in question looked like in the role. (I was actually two years older than Cross had been at the opera’s premiere but of course was a lyric baritone and not a bass, and had the several advantages of being seen costumed and in action and, even bearded, of a youthful appearance—not inappropriate for a time in history when the average life expectancy for an educated male was thirty-three years.) Not only did Menotti at the time hope to do his score again in the “near future,” but because he would plan for a run of a dozen or so performances and would himself be in charge of musical preparation as well as staging, he said he would probably double cast the title role with both a bass and a baritone, and inquired as to whether or not I still considered it a part of my repertory. Alas, we all know that in human endeavors there is much that can “gang aft agley.” By the time Spoleto USA finally got around to doing The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi, in a production honoring the composer’s 85th birthday (1996), I was long gone from the stage. Regarding the Bishop and me, to quote the immortal Ethel Barrymore, responding to the ovation following the premiere of Emlyn Williams’ The Corn is Green on Broadway (1940), in which she played the leading role, “That’s all there is, there isn’t any more.”

The Bishop hears the voices of the dead children: "Lock the doors, sister,

I cannot bear their cries. Away! Please go away!”

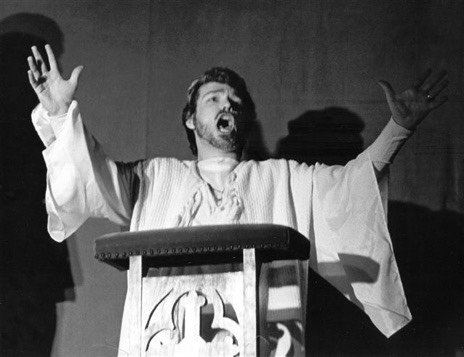

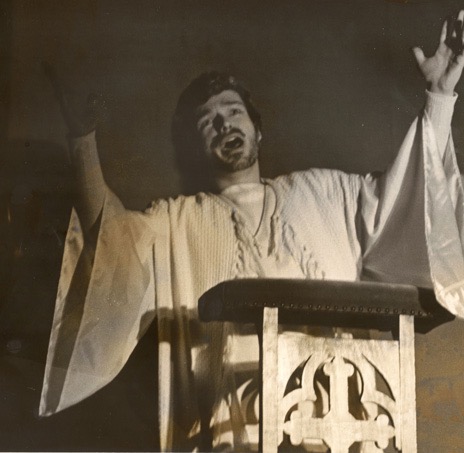

The distraught Bishop at his prie-dieu (above and below)

Near death, the Bishop relives the day he blessed the children to their doom