Part 1

Anyone telephoning our Marlborough Street apartment in Boston in the 1970s was invariably blown away if Peter was the one who answered and the caller had not previously heard him speak. The common reaction was always on the order of “Oh, wow, I sure do like his voice!” That voice—deep, warm, mellow, comforting—was the spoken manifestation of a genuine basso cantante, the real, rare thing.

Such a voice was doubtless the genetic bequest of his forebears, White Russians who originated in the area now known as Belarus (formerly Byelorussia, which means White Russia), but who were resident in Austria for some time prior to emigrating to the United States several generations before Peter’s. Along the way the family name (transliterated) may have been Bugelovich or Bugelovsky or Buglaj, any one of them evolved from ancestral identification with and residence by the River Bug, which flows from its source in the Ukraine along a portion of the western frontier of Belarus into Poland, where it joins the great Vistula River and thence moves on to the Baltic Sea. Russians produce two artistic “species” pretty much better than any other ethnic or national group: operatic basses and ballet dancers. Alas, in addition to the voice, Peter inherited another Russian trait from his antecedents: the strong disposition toward despondency. I called it “the melancholìa” or The Tchaikovsky Factor. The great composer and the young bass had more in common than just their mutual given name.

Born in Indianapolis and raised in Nashville, Peter matured physically very early (chest hair at twelve) and was a sensitive, multi-talented, vulnerable adolescent who had already begun exploring all sorts of personal and artistic possibilities when he was sent reeling by the life-altering emotional blow of his mother’s death from cancer when he was fourteen. Family members maintain that he never overcame the impact of this trauma, and that it, more than his ethnic heritage, accounted for his lifelong battle with the “demon sadness.” (Whatever the respective percentages, the confluence proved fateful.) Outwardly he proceeded onward with resolve and determination. His speaking voice not only allowed him to play old men in high school dramatic presentations but landed him the job of moderator of a local radio talk show that won a CBS Network Award. And, exploiting the fact that “I already had my low D when I was fifteen,” he anchored choirs at school and church with his pedal point notes that were lower than any of the other boys or men could reach.

He attended Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, NC, as an English major, one of our many particular compatibilities (my degree in English is from UCLA). French was our mutual second language. Both of us had begun piano lessons in childhood and both studied voice privately while in the groves of academe. Each performed in the opera workshop of his undergraduate alma mater. In fact, on opposite sides of the country in 1965, he was Balthazar and I was Melchior in Yuletide productions of Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors.

After Wake Forest, Peter enlisted and served in the U. S. Army. For part of his hitch he toured with the 3rd U. S. Army Soldiers Chorus; for the more difficult part, he was an attaché to a high-ranking officer near the front in Vietnam, documenting the events of combat both on film and in writing for the official record. He was injured in a serious accident there, being thrown from a jeep that encountered an obstacle placed on the road by the Viet Cong (fortunately not a land mine). His tour in the war zone was more than long enough to foreordain dire consequences later in his life.

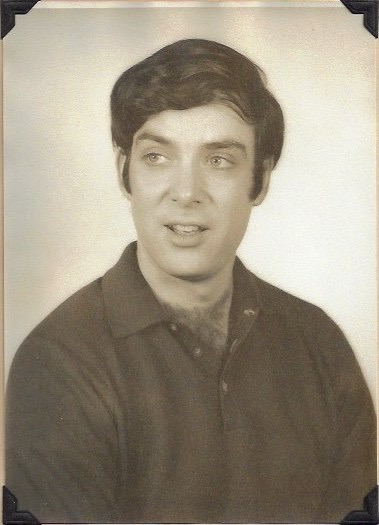

Decompression from the Southeast Asia experience took time, but when he was ready, Peter’s exceptional voice got him accepted to the New England Conservatory, where we met. He became a pupil of “Miss Miller,” the greatly beloved Gladys Childs Miller Zachareff. I first set eyes on him one day during my repertory coaching with the distinguished pianist/conductor John Moriarty. A tall, handsome, dark-haired, blue-eyed bearded fellow appeared at the door to John’s studio (all the studio doors had windows) and was motioned in. They exchanged perhaps a dozen words and a few papers of some kind and the fellow was gone, without vouchsafing a single glance in my direction. “New student of Gladys,” explained John, and we resumed our work.

The

advent of such a person on campus could not but create a stir. At the

beginning, wherever Peter sat in the dormitory cafeteria, hub of Conservatory

social life, he tended to be surrounded by hopeful admirers, gay men and

straight women trying to attract his specific interest. He was (thought I,

observing from a distance) perhaps a tad too confident in the aura of

unattainability that his magnificent good looks projected. Despite that, the

sensitive onlooker could detect an air of vulnerability emanating from him that

belied his studied presentation of aloofness. And though he clearly basked in

the attention, behind those blue eyes lurked a perceptible primal concern:

while on the receiving end of too much and too-loud laughter at his remarks and

too many oh-you’re-so-wonderful squeezes of his arm or hand, he seemed to be

asking himself, “Can any of these people be sincere?” I actually thought of the

Princess Eboli in Verdi’s Don Carlo, cursing her beauty in the

great aria “O don fatale” (O fatal gift) because it had brought her nothing but

unhappiness. In any case, this was a circus I chose not to join. A

tangential observation to the preceding is that Peter’s speaking voice alone

could be discerned through—not over but through—the din of chatter and clink of

dishes and utensils in that very resonant space. It was indeed like oil on (or

in) turbulent waters. We soon enough learned each other’s identities and could

therefore nod cordially and address each other by name when passing in the

corridor, which constituted the full extent of our interaction for some time.

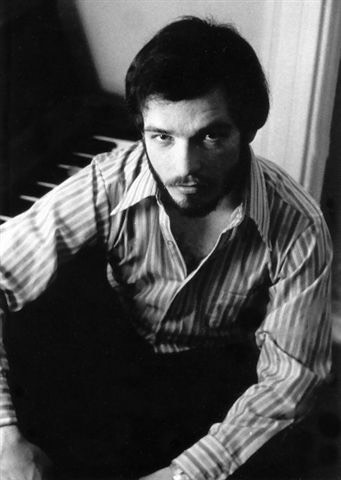

Three soprano pals of mine who shared a small apartment on St. Botolph Street—Cheryl, Karen, and Martha—liked to invite Peter for supper. (He conveyed the impression of being a helpless-in-the-kitchen bachelor though he was in fact a great cook). Martha was a fine amateur photographer for whom I had recently posed. She had one of the resulting photos framed and prominently displayed on a bookshelf, not because it was of me but because she felt it conveyed her artistic vision. In it, I am seated by a piano, looking up at the camera, sans glasses, the left side of my face in shadow. According to her report, the picture captured Peter’s immediate attention the first time he came over. He picked it up and stared at it, finally intoning in his profoundest basso, “And who, pray tell, is this?” He was duly informed. “Hmm…” (still intoning) “…obviously there is much more to him than meets the eye.” Over their meal, it was determined that, as a newbie in Boston, Peter felt inadequate to the task of finding the right place to shop for underwear—not just any underwear, mind you, but “snazzy” underwear, and he asked Karen to accompany him on his quest. She consented, but suggested that perhaps he ought to take a male advisor along as well. He thought for a moment and said, “Agreed; why don’t you ask Bruce Burroughs to come with us?”

So, yes, my first

“date” with Peter consisted of escorting him to Filene’s to purchase snazzy

undies, an event that got extended to include dinner and several more hours of

conversation. Venerable clichés apply:

“One thing led to another” (but by no means immediately) and “The rest is

history.” Some weeks later, when we were walking from my apartment to NEC after

having spent the night together for the first time, he confessed that while

watching me “so seriously sifting” through the bins of briefs in the store on

that initial day of what became our relationship, he had had an “epiphany” (his

word). “I suddenly knew that you were going to be the guy who actually saw me

wearing them.” I offered a slight emendation: “No, I was the guy who was going

to see you not wearing them!” To the

amusement of passersby, this earned me a bear hug in the middle of the

Huntington Avenue sidewalk, along with the very deep, rather theatrical laugh

(a “Ho! Ho! Ho!” to do any department store Santa Claus proud) that was unique

to Peter. This little event took place toward the tail end of winter, when we

were just barely through bundling up against wind chill. Regardless of temperatures,

at any time of year Boston was a singularly special “walking town,” a place to be gotten around on foot as much as

possible. Though we had wheels (Peter owned two

remarkably eccentric, aging automobiles, to be described in due course), still,

in daily life we walked almost all the time. Using one of the cars meant we

were taking a trip, that the distance to be traversed was too great for mere

perambulation. When out and about, myopia caused me to look at the ground

rather more than at what was in front of me, and this in turn led to the

beginnings of a stoop in my bearing—believe it or not, something of which I was

completely unaware. As we strode along, Peter would gently touch the tip of his

forefinger to the middle of my spine, saying nothing, and this would cause me

immediately to straighten up. (Decades later, that kind reminder will come into

my thoughts as I struggle to pull up out of the bent over posture into which degenerative

disc disease has permanently curved me.)

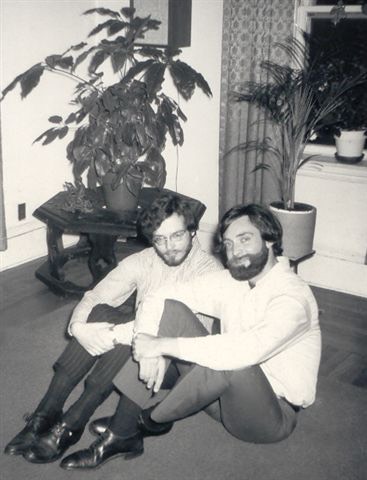

When he arrived in Boston, Peter knew exactly one person there, Greek-American Demetri (of the 3rd Army Chorus), a native son and by a considerable margin the finest young tenor in the area. As time went on, it became clear that, though not at all uncongenial, Peter was nonetheless just reserved enough to find it comfortable to rely on gregarious me for introductions within my large circle of wonderful musical friends. He liked the fact that they had already been “vetted,” as it were, vis-à-vis intellect and talent and, most of all, genuineness. Thus did his acquaintanceship burgeon beyond Demetri and the St. Botolph Street contingent that had so softheartedly “adopted” him when he first turned up at the Conservatory. Almost everybody liked him and he liked almost everybody: baritones David A., David E., and Vincent; harpsichordist Patrick (sometimes Pat, sometimes Patty Lou); cellist Frank; pianists Alan, Stephen, and Tom; Richard, the “other” real bass at NEC, and his best friend, baritone Dan, two young married men with working wives who were not in the field of music; sopranos Barbara, Sister Noël (our personal Franciscan nun, older and more worldly than anyone else in the crowd), and Marguerite; and five outstanding mezzos, Linda, Patti, Sharon, Zoila, and Marla Volovna (her two given names). Tall, raven-haired, sometimes sultry and gypsy-ish, sometimes polished and demure, always beautiful, Marla was sort of Peter’s female counterpart in appearance, and the only person who shared his background. Through her, we learned that the melancholìa does not affect the female remotely as much as the male: “Women are made to be mothers, and so, Russian or not, for the sake of the children, they cannot suffer so.” This group continued to grow and expand as Peter and I became more deeply involved with this and that performing organization. It was a splendid time, youth in the Cradle of Culture as part of a colony of talented, starting-out, rarin’-to-go musicians with limitless possibilities. Such eras in life are all too brief and seldom properly understood and appreciated while they are being lived.

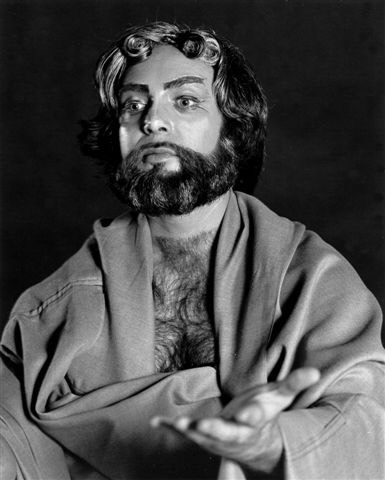

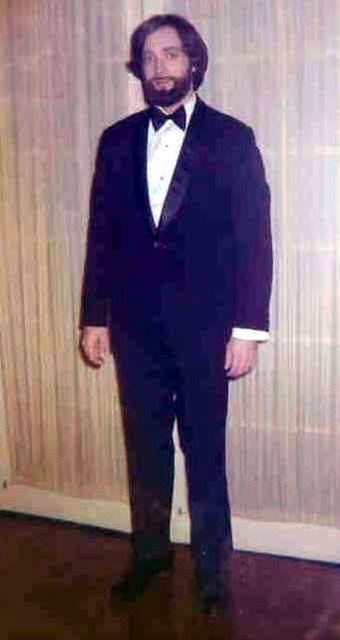

Peter performed small parts in Sarah Caldwell’s Opera Company of Boston production of Berlioz’s Les Troyens and in The New England Chamber Opera Group’s presentations of Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi and Weill’s Down in the Valley, in all three of which I also appeared. Larger roles in which he was most impressive were Candy in the New England Regional Opera’s East Coast professional premiere of Carlisle Floyd’s Of Mice and Men, and the god Jupiter in the Chamber Opera Group’s offering of Gounod’s Philémon et Baucis (sung in English as Gift of the Gods), given in a double bill with Busoni’s Arlecchino, in which I essayed the title role. As the photograph at the top of this page attests, it required no suspension of disbelief whatever to accept him as the head god of Roman mythology. (Except for the golden curls and the faint gold streaks in his beard, all the hair was his and he towered over the rest of the cast because of his six-foot-plus height.) When the director of one of the above-mentioned opera companies (NERO) first laid eyes on him, he cast Peter as the Giant in Henry Lasker’s children’s opera Jack and the Beanstalk without hearing him sing a note. “Some of our roles have very specific physical requirements” went the explanation. In his season as an Apprentice Artist at the Santa Fe Opera, Peter covered the large role of Daland in Wagner’s Der Fliegende Holländer as well as the cameo part of the doddery old gardener Antonio in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro and the brief but really-shows-what-you’ve-got role of the Friar in Verdi’s Don Carlo, a true indication of the range and versatility hoped for from a young bass with his vocal endowment.

Oratorio-wise, he was in demand for the bass soli in Haydn’s Creation. No one but no one could intone the hilarious line “…creeps with sinuous trace the worm,” ending on that prized low D, like Peter. It was a bit of excusable exhibitionism, as Papa Haydn had compassionately instructed the bass to rise from the low A to the D above, not go to the one below. When we worked on the score, Peter asked me if it would be alright to descend rather than ascend. I reminded him of the words of the great soprano Luisa Tetrazzini, who, when queried about why she interpolated so many unwritten high notes, replied, “When-a you got-em, you show!” Upshot: that philosophy would do just as well for low notes.

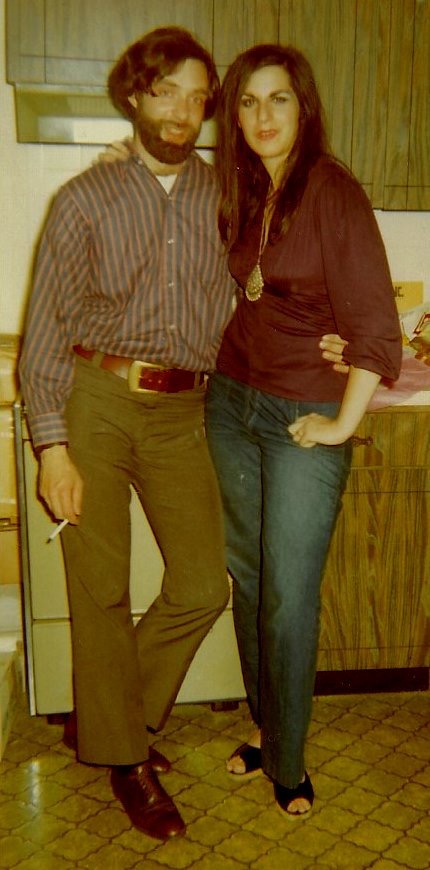

In his twenties, before a lifelong problem with his weight

manifested itself, when he was bearded, Peter gave the appearance of being the

epitome of machismo, though that was pretty far from his actual nature. When smooth-faced,

he was altogether boyish and even had a bit of the imp about him (though he

corrected me: “I’m too big for an imp”). One army buddy found the difference so

great that he saw a Jekyll and Hyde dichotomy. That was a ludicrous comparison,

though Peter indeed seemed more imperious—and much older—with facial hair than

without. Asked about his beard by our landlady, he made the remarkable

statement that “In the theater, this is money.”

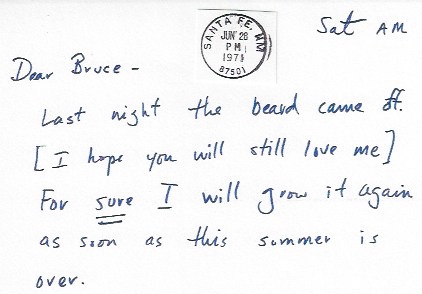

I cannot verify the money part, but will attest to the fact that when I first heard him sing he had just turned a luxuriantly bearded twenty-six and that those carefully shaped and trimmed umber whiskers imparted a gravitas to his appearance that perfectly matched the deep tones he emitted. Later that year, when the Santa Fe Opera required that he be clean shaven, he was the same man, sending forth the same sound in the same kind of music, but the effect was clearly diminished. The incongruity of the depth of sound he produced issuing forth from that youthful, cherubic countenance was lost on no one. “I didn’t expect such a deep voice to come out of you,” observed one clueless fellow apprentice (had he never heard the man speak?). This distressed Peter mightily. He felt laid bare, too “revealed” when “showing his face” (his designation). The beard was his “beard,” as it were. Thus, the true difficulty had not so much to do with the effect of his singing under one or the other hirsuteness circumstance, but rather that there was what is nowadays referred to as a “disconnect” between the person Peter really was and how he wanted and needed to be perceived. Whether it crept inside “with sinuous trace” or otherwise, it became a worm in his psyche. As the moment of “separation” impended, he wrote, “Wish you could be here to shave it,” clearly feeling the procedure would therefore be less traumatic to undergo, and then when it was accomplished he worried about what my reaction would be. He believed he got more attention, respect, and admiration when he was the full-grown dog rather than the smooth puppy. I have to say that this proved sometimes to be demonstrably the case. It wasn’t his imagination, but it also wasn’t always to his advantage.

One balmy May New England evening, when walking to a NECOG rehearsal on a main Boston thoroughfare, we were suddenly accosted by a passel of earnest young men, all in shirt sleeves (rolled up), neckties, navy slacks, spit-polished loafers, all virtual clones of each other with regard to height, appearance (white, good-looking, well-groomed) and a scary uniformity of demeanor. They pushed me out of the way—literally, not figuratively, pushed me aside—to get to Peter, whom they surrounded at once. He could move neither forward nor back, indeed, in any direction at all. They wanted that tall, handsome man with the beautiful hair, the sensitive blue eyes, the effulgent beard, the deep voice (they had surely heard him speaking as we almost passed them), wanted him as a recruit to their cause, wanted to train him to go forth into the world and recruit others, ensnaring them through his beauty and his voice. Just at the mere sight of him, they had the rest of his life all planned out. On a table near where we were stopped in our tracks were stacked multiple copies of L. Ron Hubbard’s treatise Dianetics.

I saw this encounter as sinister from the get-go. A few years earlier, I had been exposed to Dianetics by a pushy singing colleague in Los Angeles who had swallowed hook, line, and sinker its nominal message and the “religious” belief system—Scientology—that grew out of its philosophy. I knew, for instance, that Hubbard believed any “human aberration”— homosexuality was high on his hit list, gay people being, in his view, entirely “untrustworthy” because we were “perverts” and “sociopaths”—could be eradicated by intensive counseling and that enlightenment was impossible until the eradication had taken place. At the time, Scientology had already been extremely controversial (to put it mildly) in the court of public opinion, in courts of law, and in both the news sections and on the editorial the pages of all the major international current events dailies and periodicals. I had a notion of what we were up against, knowing that these tenacious lads had gone through a grueling “educational” process and believed that if they had any problems of any kind prior to so doing, such impediments were now entirely “eradicated.” Equally certain is that contact with any person or information that might indicate their new state of enlightened being wasn’t genuine would be anathema and to be rejected at any cost.

While I was trying to figure out how to assist in getting him out of the situation he was in, Peter at first basked so happily in the attention that he didn’t seem to grasp how intrusive and inappropriate were the questions with which he was being bombarded, and he tried to answer them seriously (“Do you go to church?” “Are you religious?” “Are you happy in your life, or are there too many things that don’t work for you?” “Have you ever spoken with anyone of true understanding about leading your ‘real’ life?” and so many more, all of which I could hear as well). By the time he realized that he had been entrapped, he almost simultaneously discovered that his wonted mahogany-toned smooth talk, usually effective and quickly so, would not serve to deliver him from his captors on this occasion. A look of panic appeared on his face. He was staring at me with what was clearly a silent plea of “Help me!”

I waded into the little knot of humanity: “I’m sorry, guys, we’re on our way to a rehearsal, and you’re making us late.” One of them stepped right in front of me, blocking my path to Peter: “Um, we weren’t speaking to you, and for your information he doesn’t need that rehearsal, whatever it is. He needs something far more important.” Another fellow joined this one, and together they skillfully blocked my every move, like linesmen on a football field, moving this way and that as I tried to get around them.

At last, I did what any feisty 5’6” Scorpio would do to rescue his non-confrontational 6’3” Sagittarian lover from peril: I hit them with the truth, bearing in mind what I knew about the cult’s stance on gay people. “OK, guys, we’re gay. That big he-man over there, he takes my [followed by the crudest, most offensive possible description of their captive’s favorite sexual activity].” The officiousness drained right out of them. They stared hard at Peter. Surely, surely, a man who looks like that can’t possibly be queer let alone indulge in the activity described. He was scared enough to decide that he had to chime in, too: “Yeah, and I love it.” Shudders of revulsion all around (some of which, I thought, were just plain bad acting). I guess they did a split-second assessment, without oral communication, of the likelihood of “retraining” Peter into heterosexuality and loathing of his own former self, and decided, with however many heavy sighs of regret, that he wasn’t an ideal candidate for their indoctrination program after all. They took their hands off him and he was allowed to move forward. He did so slowly, not wishing to appear to be running away from his potential, now thwarted kidnappers. We walked on a short distance in complete silence, not looking back. Finally, he said, “Thanks, Mouse. I guess I should call you Mighty Mouse from now on.” “Not necessary. I’m fine with just plain Mouse.”

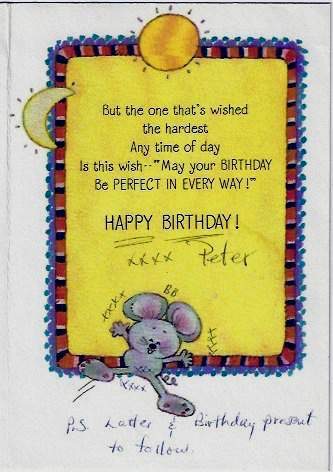

I had earned my sobriquet in Santa Fe. Initially, it had nothing to do with the difference in our heights (or any other anatomical comparisons). There was one night when Peter went to bed long before everyone else because he had a very early rehearsal next morning. I tagged along with some of our friends (the Boston contingent this particular summer numbered no fewer than eleven) to a local cantina and didn’t get home until the wee hours, when I sneaked into bed without disturbing him. When he awakened to find me next to him, he asked “When on earth did you get in?” “About two o’clock.” “Well, you were sure quiet as a mouse!!” That’s how it started. Later on, it got expanded to a once-in-a-while designation of “Cheddar the Mouse” because I happened to be partial to extra sharp Cheddar cheese. Our eventual couples counselor in Boston, Rev. Don, thought it was negatively significant that Peter had to “diminish” me thusly. I felt it as a term of endearment and never minded being Mouse. Peter, however, took the criticism seriously and, to share any possible stigma, began to refer to himself as Big Mouse and to sign himself “B. M.” in the kind of private notes that a spouse leaves taped to the refrigerator door or the bathroom mirror. In our musical environment, those letters were both seen and heard rather frequently (they meant Bachelor of Music to the NEC population), but when I reminded him of their biological significance to most people, he ever thereafter wrote the whole title out, or at the very briefest, “Big M.” It was probably inevitable that I would finally become Little Mouse, at which point the “Big” and “Little” indeed constituted commentary on his height and my lack of it. Every holiday, special event, or birthday card the man ever gave me had a mouse on it, and if he couldn’t find one that exactly suited him for a given occasion, he’d draw the mouse himself. One year, when we were a couple thousand miles apart, my birthday card not only had a mouse on its face page, but one inside as well. Peter surrounded the latter with symbolic kisses, most particularly including the strategic place where the little guy’s private parts would be if Hallmark mice were allowed to have them.

By our definition, the Scientologists were an incident, not an adventure, but one that prompted a good bit of soul-searching regarding aspects and abuses of flattery—to which Peter was exceptionally susceptible—as a means to a result desired by only one party to the flattery and as an end run around rational thought at a given moment in time. He was neither stupid nor blind, but remained incompletely able to see what had happened and what ego mechanism was instantly triggered as his reaction to the sudden outpouring of unexpected admiration—admiration with a catch—from total strangers promulgating a fanatical, idiosyncratic agenda.

Our adventures were many and varied, as were our residences: two lovely apartments in Boston, one in a newly renovated and thus up-to-date former office building, one in an old brownstone (where we occupied the whole second floor); half of an old converted carriage house that he co-owned with his dad’s older sister in Bethany, CT (outside New Haven); an ersatz “Swiss” chalet in Aspen; an adobe guesthouse in Santa Fe; a two-room flat in what was clearly a house of ill repute (not quite “the best little whorehouse in Texas,” but it came close!) in Fort Worth; and stints in the rooms where we grew up in our family homes in Los Angeles and Nashville. Most of the peregrinations required for this gypsy life (movement was always in pursuit of artistic or educational goals) were accomplished in Peter’s rickety, slightly banged up, how-was-it-still-functioning-with-so-much-mileage-on-it old Volkswagen Beetle, no match for the huge semis with which we ran in tandem on the nation’s major highways. If he straightened up completely in the driver’s seat, Peter’s head would touch the roof of the little car. He also had an ancient Buick Skylark that, mechanically, was even less suited to cross-country travel than the Bug (though it was so much roomier!), meaning it stayed parked at the carriage house.

Peter was both tenderhearted and a closet romantic, but he had an innate reticence where expressing his positive or loving emotions orally was concerned. He was nonetheless filled to the brim with them. Melancholy, angst, and depression were more evident in his demeanor, behavior, and outlook, though these, too, were usually denied expression in words. How much of this difficulty was native to his character and how much the result of formative experiences is eternally moot. From the very early onset of puberty he looked and acted much older than his actual years. He knew right away that he was interested in and interesting to older boys. This aroused the greatest possible disapproval at home: “My mother tried to beat the gay out of me,” he said. Her untimely death removed forever the possibility that she would “come around” to acceptance the way his father eventually did. For a long time Peter suppressed what turned out to be a considerable reservoir of anger, but there was no way to keep it from asserting its covert influence in his life.

When it came to the written word, however, his deepest feelings were a different matter altogether. His letters (there are many) often prove to be extraordinary in their openness and lack of reserve; the act of putting it all down on paper seemed to be cathartic. Yet and still and despite all these factors, there were indeed times when he couldn’t down the impulse to acknowledge his love overtly, and he always seemed lighter of heart, even genuinely uplifted when he did so. In these moments he acknowledged how much better he felt, and wondered out loud what on earth it was that so firmly constrained him from “turning loose” (his words) his happiness. The many years that have passed have hardly dimmed such cherished memories as that he loved my green eyes and in gift-giving always challenged himself to “match” them, or that after being assigned a particular song for an audition, one that clearly got to him in a special way, he decided it was “our song,” and he would sing it to me often in his beautiful sorghum-hued tone. This was “My Cup Runneth Over” from the musical I Do! I Do! and with it he could reduce me to a puddle:

Sometimes in the

morning when shadows are deep

I lie here beside

you just watching you sleep

And sometimes I whisper what I’m

thinking of

My cup runneth over with love

Sometimes in the evening when you

do not see

I study the small things you do

constantly

I memorize moments that I’m

fondest of

My cup runneth over with love

In only a moment we both will be

old

We won’t even notice the world

turning cold

And so, in these moments with

sunlight above

My cup runneth over with love

My cup runneth over with love

With love

[To be continued]

Because this remembrance turned out to be a

far more emotionally demanding undertaking

than originally anticipated, a bit more time

than initially planned will be required for it

to be completed. Please bear with the author

and return later on to read the finished piece.