Among musicians, mine is not such an unusual story. I think that for most of us, it has always felt as if music and destiny are synonymous and that somehow it has all been determined long before birth. Therefore, regardless of difficulties and obstacles that invariably arise—those are where the tremendous individuality of each journey resides—the artist is from the beginning set upon an inevitable path. Regardless of how early or late the path is recognized, the uniqueness of each journey is as foreordained as its end result always seems to be in retrospect.

Because of the geographical exigencies of my father’s stint (as a Pharmacist’s Mate First Class) in the U.S. Navy, my life began in Seattle, though Maryland (and earlier, Virginia) had for generations been the family home. I was taken back to the Old Line State on a train by my mother when I was six weeks old, and because I had to turn down an invitation from general director Henry Holt to sing at the Seattle Opera in the 1970s, I’ve actually never again seen my birthplace. Hagerstown, a quaint, lovely, warm, wonderful little burg (1950 population 32,000) in the Middletown Valley of Western Maryland, is where my roots were put down. I feel them deeply. In recent decades the encroachment of commuting Washington, D.C. bureaucrats as residents has truly spoiled the ethos of the place, but until well into the 1960s Hagerstown had as much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries about it as it had of the twentieth. This was something that appealed to my basic nature to a degree beyond the power of words to describe. Despite all subsequent experiences of a cosmopolitan nature, it is the small-town English-German Protestant (Lutheran) background (without its religious implications) that, for better or worse, most informs the character of this particular artist.

But this isn’t a genealogical or historical profile. Forgive me if I resort briefly to the third person in talking about the earliest years. It really does seem as if I am speaking of someone else—an entity both long ago subsumed into and yet eternally set apart from the senior citizen writing at this moment. (Further exploration of this dichotomy can be found in the “Underneath it All” chapter of the “Stage Memories” section on this website.)

The little boy, as soon as he was able to sit up on his own, was observed rocking back and forth to the rhythm of whatever music happened to be playing at a given moment on the radio or the phonograph. That is, the exact rhythm. Clever caretakers learned early on that if he was colicky or wouldn’t go to sleep for any reason, just to sit him up in his crib and put on fast music. He seemed to be constitutionally unable not to move at the dictated speed, so he would rock himself into exhaustion trying to keep up with the tempo and eventually just fall over, out like a light.

At the age of about three and a half, the little guy was ready to kick it up a notch. A visit to the home of anyone who owned a piano found him crawling up on the piano bench, sticking out his pudgy index finger, and playing melodies (the first was “America”) without error from the first time onward. He could start anywhere on the keyboard and go note by note, making no mistakes, though he hadn’t any discernible way to know about intervals, the difference between whole and half steps as represented by black and white keys, and so forth. The parental units were slightly annoyed by this innocent exhibitionism, which could be disruptive to the chitchat of adults, while other onlookers found themselves rather blown away by it. “Give him lessons!” became a frequently heard exhortation. Also, there were requests, usually for hymn melodies, and especially for Christmas carols during the holiday season, when the questions would morph from “Can you play ‘A mighty fortress’?” into “Can you play ‘O little town of Bethlehem’?” A particular favorite at the wintry end of the year was “Joy to the World,” because that little index finger would really have to travel! Witnessing this, the boy was informed years later, constituted superlative live entertainment in the day when no homes in the municipality yet had television.

Lessons were deferred until after a relocation to Southern California (more paternal geographical exigencies, this time of employment). The first piano teacher was Edwin Carver, a gifted young pop pianist who tickled the ivories for the Curt Massey Show, a daily half-hour program on local TV in L.A., on which he and a small instrumental ensemble accompanied Texas baritone Massey and his singing partner (also from Texas), “Liltin’” Martha Tilton, famous and admired performers of the time. Eddie was a chain smoker who blew an immense cloud of heavy blue haze around me (I’ll revert to first person here) every week as he sat writing out chord patterns of the most current pop songs for me to learn, a process that apparently fulfilled all of his other students but did nothing whatever for my real musical inclinations. On a shopping trip one day with my visiting paternal grandmother and step-grandfather, I cajoled the former into buying for me an anthology of piano music, G. Schirmer’s “59 Piano Solos You Like to Play.” Its contents were all classical music, almost all difficult, and according to my naked-eye perusal of the individual selections, only about a third seemed beyond my capacity at the time. I presented the book to Eddie at my next lesson and said, “I’d like to work into this gradually,” as assertive as my seven-year-old self could venture to be. The first assignment was a movement from Mozart’s Piano Sonata in A, K. 331, commonly called “Rondo alla turca.”

I was surprised to discover that not only was it not difficult, but that it was well enough within my means that I could move on to something harder right away. Eddie thereupon decided that I needed a more advanced teacher (that is, one who would revel in hearing Mozart rather than “Mr. Sandman”). I’ll owe him forever, because he was a perfect instructor for a beginner, our divergent musical tastes notwithstanding. He inculcated in me fundamentals of technique that served for the rest of my days as a pianist and that, thank goodness, withstood the ministrations of the next teacher, an “artistic” rather than technical pedagogue, who indulged all my desires to tackle Bach, Beethoven, and Chopin, but had no idea of what one did with the hands and arms in the course of playing such music (he was very good at designing the fingering for difficult passages, however). As for Eddie, who lived with his wife and small children just a few doors up the street from us, his death at age thirty-five from lung cancer, four years after we stopped working together, broke many hearts.

The piano at home, an old Lester (“made in Philadelphia”) upright that was purchased for a song from a “used piano” warehouse where I selected it from among dozens of superannuated instruments I tried out, was only briefly positioned against the south wall of the living room on Inglewood Boulevard. It was soon enough placed out of sight in this small musician’s bedroom because between its boxy shape and mottled dark purple (!) finish it wasn’t comely enough to be seen among the much nicer pieces (Mom was into very tasteful, non-hokey “early American” maple furniture), and thus became a private and wonderful personal possession. Practice was behind closed doors, unseen if hardly unheard. A haunting photograph of this long-gone era is of the piano in the bedroom with volumes of Chopin lined up the width of the lid closed over the keys, the composer’s name in large letters treated as a sort of beacon by the camera’s lens.

The “artistic” gentleman who succeeded Eddie Carver was Robert L. Tusler (“Tus”), organist and choirmaster of Grace Lutheran Church, Culver City, where the Burroughs family worshiped. At the time I began piano lessons with him, I was already the soprano in the church’s boy choir with the highest and strongest voice. This brought the reward of frequent solos and anthem after anthem in which I was perched alone on some altitudinous obbligato line. The important point to raise here is that all this came to pass in the year after I first heard the lady with the most beautiful voice in the world and became completely enamored of and devoted to both her and opera (see the “Zinka and Bruce or Love at First Hearing” chapter in the “Milanov Biography Project” section). I was far too young and innocent to have any ideas about gender identity, the sexuality of the voice, or any other such advanced considerations. Though I longed to be a tenor when my voice changed, I wasn’t unhappy with my pre-pubescent boy’s voice and its easy high notes (up to what I related to at the time as Lily Pons’ high E-flat, but much stronger).

As a soprano, I just sang like Mme Milanov, soaring and floating at will and without inhibition. For the all-too-brief period during which a boy can produce such a sound, people came from all over to hear it. Persistent attempts were made to recruit me for the local Episcopal Diocese’s choir academy, an all-boys school, but my parents thought my interests eccentric enough without indulging them to that great a non-mainstream extent. Professional singers and choir directors were constantly commenting on my extraordinary legato and long breath. I had no personal concept of either, but just replicated to the best of my ability what was to me obviously the right way to present vocal music—the Milanov way. The soaring and floating didn’t survive the onslaught of testosterone—the deepened male voice has to roar and ring, anyway, altogether different matters—but the legato and breath line remained as permanent assets.

It’s too often the case that those responsible for keeping a church going—laity and clergy alike—presume to know what God has in mind for this or that congregant, especially one too young to be able to mount a defense. My talent as a pianist suggested to both my teacher, the organist-choirmaster, and to the pastor of Grace Lutheran that I might be particularly useful to the parish at times when Tus was unavailable. It was therefore decided on my behalf that I would study the organ. I had no interest in doing so, being absorbed enough with piano and my choir singing, but “No, thank you” was not an acceptable response to the powers that were. The decree came down, as if from Herod Antipas, that I would study, whether or not enthusiastic, so that I could be the church’s substitute organist. Little if any negotiation took place with the desired object directly. My parents’ senses of duty and obligation, not to mention their egos, were duly plied and stroked. They succumbed to the pressure, and the matter was out of my hands. Difficulties abounded. At eight, I was too short to reach the pedals—in fact, had to be seated on a Los Angeles telephone directory in order that my limited arm span could encompass all the keyboard manuals. This meant that I had to incorporate as much of any given pedal line as I possibly could into the keyboard part of a score, something I did without too much thought (and uneven success, needless to say). However, professionals who came in droves to play the church’s new Holtkamp organ—“first Baroque organ west of the Mississippi” was its sobriquet from the time Tus inaugurated it in a recital on which I played a single selection—thought my “transcriptions” made me a “genius.”

I had to give up tremendous amounts of social time with my friends in order to be taken to the church to practice (there was hardly room for a pipe organ in the bedroom alongside the old Lester!!), which peeved me in the extreme. No matter how dearly I loved music, I was very much desirous of a “normal” life where school and friends were concerned. The Rev. William Herbert Blough was a particularly tough character with regard to demanding discipline and respect from the youth of his congregation, qualities he equated with doing exactly as he said and accepting his judgment in all matters as if it were in fact biblical mandate. And so my talent was exploited, the old canard “God gave it to you, you owe it go God” falling freely and in accusatory tones from the lips of everyone over twenty-five. The economic advantage of having a child able to do an adult’s work as well as the adult—a child who could be chastised and reported to his embarrassed parents if he dared suggest that payment was as much in order for him as for the pastor and the actual organist—cannot be calculated. Great sums of money were saved by not having to pay me anything. My parents, though, had no choice but to subsidize the lessons (which were not provided gratis by Tus in spite of the design behind them). They even sprang for a couple sessions with the First Organist of the Vatican, Fernando Germani, when he came on a U.S. tour and an audition was arranged for the organ “prodigy” with one of the instrument’s historically important players. Though perhaps no older than I am now, the maestro seemed ancient to me. He was kindly and had a few suggestions but spent most of his time patting me on the head saying, “Che bello!” More than half a century later, the sole existing recording of me going at it on that Holtkamp proves to be quite impressive. But at this point, unlike my other musical accomplishments, I have no sense of identity with it at all.

Funny how what God always and invariably wanted was exactly what was convenient for the mature religionists of Grace Church, never for this little keyboardist, which ultimately instilled in me a natural, permanent, and entirely healthy suspicion of all earthly certitude regarding heavenly intentions. The more definite and “beyond all doubt” the tenets of responsibility that were ostensibly mine to obey, the less to be trusted was the person foisting them on my head—that’s what the twelve-year-old musician thought. The sixty-something result of those early experiences finds yet no reason to disagree. (In later life in the three great cities in which I lived and was a musician, whenever I darkened the doors of a house of worship to practice my art, you’d better believe a check was forthcoming immediately after.)

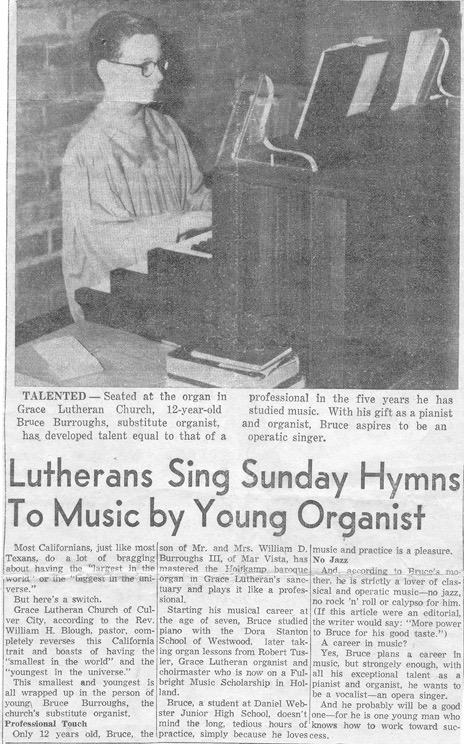

By twelve, my voice had lowered to alto and I was no longer the darling of boy soprano enthusiasts. To continue to be a drawing card for special occasions, I had to be publicized as an organist. Now able to reach the pedals, I could manage not only difficult works by Bach but, among other true loves among composers for the organ, some of César Franck’s great pieces as well. These I programmed as preludes, offertories, and postludes on the days I played services. The hallowed American Guild of Organists, perhaps also with an eye to its public relations image, had already opened its sacrosanct membership rolls to me a few years before, making me the “youngest member in [its] history.” There is a panoramic photograph of the attendees at the 1955 national convention of the AGO, which was held at Long Beach, California. Among the large number of lady organists with prim high collars and proper hats, and the men in suits and neckties, folded handkerchiefs correctly peeking out of breast pockets, there stands a slight, nerdy-looking ten-year-old kid in glasses, short sleeves (no jacket), and a string tie. Everyone was kind and interested when they found I could discourse upon the merits of Buxtehude or Leo Sowerby with equal authority. Eventually, Pastor Blough called the local newspaper to crow:

From The Evening Star News, Culver City, California, 23 October 1957

This little exposition was placed at the very top of the Culver City paper’s second front page, right by the banner head, as though it were important news. The piece was picked up by major papers, including the Los Angeles Times, always with its several errors but also always without the photo. Chronologically, Tusler preceded Stanton, whose name was Doris, not Dora, and who didn’t have a “school” but a private studio. She was a fine technical teacher, too, exactly the right person at the right time. When Tus left to pursue his doctorate at Utrecht, Doris followed him into the organist-choirmaster post at Grace Lutheran, and my organ studies mercifully ended. Concentration could return to the piano. (At grammar school “graduation” ceremonies, I chose to perform thorny, percussive pieces by the Brazilian composer Octavio Pinto and the Argentine Alberto Ginastera because the final social studies unit of the sixth grade had been South America.) I still played for church services, of course—the publicity above dates from the Stanton era, in fact—but much more on my own terms. Occasionally I even refused to have my time commandeered on short notice, and got my wishes respected…but not always.

Sometimes, extraordinary measures had to be taken to exert one’s will over those of all the grownups. There was a particular operatic Saturday that required all my scant dozen years of accumulated ingenuity in order to prevail over stronger forces. On Friday night, church minions had called to announce that my presence would be required the next morning and early afternoon for some function of the Luther League (organized teenagers in the Lutheran church), to play both piano and organ. The fact that at exactly that time I desperately wanted to hear the Metropolitan Opera’s broadcast matinee (commencement time 11:00 AM PST) was of no concern whatever to the “You owe it to God” crew. It wasn’t even to be considered. I knew I had to be taken suddenly ill in order to avoid missing my great listening opportunity. Accordingly, I arose early, went to the kitchen, and with some courage, over and over inhaled as much black pepper straight up the nose as I could possibly manage with each breath.

The effect was immediate and devastating. I thought I would choke (or burn) to death, but the instant uncontrollable sneezing and the sudden development of copious amounts of mucous were just what was necessary. The red, rheumy eyes and appearance of being flushed and feverish were to the good as well. The burning and real misery were not put on. The constant need to wipe my nose, cough, and drink water was not manufactured, either. The Luther League lost its patsy and I stayed home in bed, nearby radio at the ready. Mom was not easily deceived, however—doubtless those telltale black grains that continually emerged with the mucous onto the Kleenex suggested ample reason for skepticism over my sudden “bad cold”—and with an air not to be gainsaid, she stepped to the precious little electronic box on my desk and announced in her strongest you’d-better-do-as-I-say tone, “You’re too sick to bother with the opera, you need to sleep,” and switched it off. She closed the curtains, darkening the room, and went out, shutting the door behind herself. I stayed put, allowing an ample interlude for a surprise reappearance. When none transpired, I crept as quietly as possible to the desk, moved the radio from its usual spot to a place within and at the back of the kneehole, next to the wall, crawled into the tight space, of necessity curled up into the most uncomfortable position conceivable, and squashed my right ear against the small speaker, whose volume I set at the lowest possible audibility level. Locked in that sense-numbing position I heard and gloried in the magnificent 29 December 1956 broadcast of Verdi’s Ernani. Nobody but nobody was going to deny me, the boy who had already declared his intention to become an opera singer, live time with my Zinka!

But soft! I hear the inimitable voice of Elvia Allman, intoning the direction “Speed it up a little!” to the unseen person in charge of the conveyor belt that’s moving those still-to-be-dipped candy nougats past Lucy and Ethel at too leisurely a pace. Let’s see if I can manage, contrary to my entirely nineteenth-century writer’s nature, to move this profile along a bit, for the sake of at least eventually bringing a conclusion into view (it’s already way too late to say “for the sake of brevity”).